Baltic Horizon Fund is in bad shape

I must admit to being a bit surprised that no unit-holders in Baltic Horizon Fund (BHF) contacted me in the last week. Perhaps what I wrote didn’t reach that many of them or I didn’t make myself as clear as I could have.

My last post, if it wasn’t totally obvious, was written out of an economic interest in Eastnine and done after only a day or so of research. I have no clue whatsoever what kind of discussions Eastnine is in beyond what they have revealed publicly. In fact, I have never even spoken to Eastnine’s management except through written questions on conference call webcasts.

After spending a couple of hours reading up on BHF, this situation seemed to potentially fit as an acquisition. A lot of what I do is thinking about possible accretive deal-making, as may have been evident from my series of posts about a certain Latin-American telco earlier this year.

A public indication against my idea is that Kestutis Sasnauskas (CEO of Eastnine) subsequently said in an interview with the podcast Kvartalet that they are looking mostly towards Polish acquisitions. So take that for what it’s worth.

No matter, this post is not about a potential or not-so-potential deal with Eastnine. Instead, prepare for an info-dump about Baltic Horizon Fund. I will try to keep this as simple as possible, but it will get quite technical at points (some would say boring).

Alright, enough preamble.

Admittedly, before last week, I had only a passing familiarity with BHF. Since then, I have had time to go through more of the history and read the recent bond listing prospectus in more detail, and what I have found has not exactly made more bullish on the outlook for the fund. I don’t take lightly writing negatively about something — in over a decade of occasionally writing about stocks publicly I have almost never done it, at least not in any comprehensive way. However, in this case the pricing of the units does seem to indicate that either the illiquidity or the investor base is keeping the price inefficient to the upside.

Let me be clear upfront about what I think: there is imminent risk that unit-holders of BHF get diluted or even wiped. Best case, from that perspective, the fund can sell some assets and limp on for a while. The time is quickly running out for that, but even if they managed to, it’s unlikely that it would be the best long-term outcome for unit-holders. Barring large interest rate cuts, and I mean probably on the order of 2-3%, the fund is way too highly levered and has too expensive financing — part of which they are locked into with the latter part of the bond issue — even should they be able to offload assets. An illustrative example is that management predicted that the Duetto sales would take the fund to 49% “net LTV” (this is excluding the bond debt) which ended up being 53%. Actual loan-to-value including the bond is 60% per the half-year turn and 57% after partial repayment of the bond. But I’m getting entirely too far ahead of myself.

Firstly, I want to address the alignment of management with unit-holders. The compensation scheme of BHF is as follows:

What this means in plain language is that discount to NAV doesn’t matter at all to the level of fees, as long as it isn’t realistic to trade close to or above NAV (something that generally only happens in the listed RE sector for brief moments during boom years and is almost unheard of for closed-ended funds). This incentivizes growing the assets under management over shareholder returns. If not possible to grow the assets, management should have an interest in keeping the assets for as long as possible, no matter what the exit value happens to be for unit-holders.

A counterweight for this incentive would be if management was heavily invested in the fund and so would earn just as much money from the performance of the assets as from the management fees. This seems not to the case. While there is some owner interest among management and board members, it hardly seems like enough to offset the asset-gathering incentive of the comp scheme.

Unit-holders should be aware of this when evaluating the chosen strategy of BHF to alleviate its leverage situation.

This is essentially the same strategy that was chosen by some of the largest listed RE companies in Sweden. But in those cases it was more out of sheer economic necessity. SBB can't conceivably sell themselves in their entirety to another entity because they are too big and nobody wants to pay enough for the underlying assets as to cover the debts and give something to the equity. Additionally, they are locked in by a lot of cheap financing which could be forcibly called in a takeover due to change of control clauses, which decreases the value of the company to any buyer compared to its value to current owners.

So, zombie company is the path of least resistance until they eventually get payment problems or a bond cliff that’s too large to handle. This transforms the equity into something akin to a far out of the money call option on the underlying assets. That is: default is most likely but there is a chance for recovery as long as the equity is alive.

For a smaller entity that is not overwhelmingly financed by bonds with change of control clauses and where the underlying assets are less impaired this is not the necessarily the best course of action. So a strategy of slow divestment may be a suboptimal strategy if you instead can solve the issue by selling everything. It’s also certainly a worse strategy if it’s really hard or impossible to sell individual assets near their stated values and you are facing imminent debt maturities. So let’s begin with those:

7.5 million was paid back on the bond after the Duetto sales. This leaves 12.5 million on the bond which is due in May 2024. This sum by itself is impossible to pay back without selling either Europa SC, CC Plaza and Postimaja or Galerica Cetnrs or at least two other assets. This all of course assumes that the assets can be realized at appraised value, which is in severe doubt. Europa SC is unique in the portfolio in that the LTV on it is as low as ~24%. Postimaja+Plaza is at 47% and Galerija Centrs 45%. So in a sale, there is the most room to take a haircut against stated value, because that would still leave a lot of cash for debt repayments. Also, the other retail assets are in need of refurbishments, as per BHF’s own statements, and that would need to come additionally out of the pocket of any prospective buyer, limiting their bidding price.

Eastnine might be interested in Europa despite it not being an office building due to its proximity to their assets. However, it doesn’t make a lot of sense to pay a high premium for this asset compared to the office deals that are available with higher cap rates, much less variability in rental income, and less investment needs over time.

BHF has likely been trying to sell assets for at least a year, so the fact that no retail assets have been sold yet does indicate that interest rates have hurt bidding prices for them. If they were able to sell the assets with lower cap rates at decently close to their valuations on the books, that would ease the burden of interest rate costs much more than the fully let high cap rate Duetto sales did. We know that eager sellers have by and large been forced to sell the best cash-flowing assets, in all likelihood because bids for lower yielders are further off stated values. Thus, there is adverse selection in what is left on the books while appraisers are slow to adjust.

As seen above, Galerija Centrs has an upcoming maturity in January and has as far as we know not been renewed yet as of mid-October. This is significant because the debt is currently breaking the interest rate coverage covenant.

It therefore seems far from certain that this loan can be rolled in its entirety, especially since cost of debt has not decreased in the intervening period. Maybe the bank is leaning on BHF to instead sell the asset after giving them a waiver; this is unknown. A quite plausible positive scenario of getting 25 million rolled would leave another 5 million for BHF to fill through divestments, meaning they will need in total 17.5 million from divestments in the coming months to avoid default. Part of that can be covered by some of the 10.7 million on hand that they have after the partial bond redemption, although how much that can be used is unclear. There is a loan repayment schedule that corresponds to 1.5% yearly or 1.675 million. There is also the management fee of 1.5% on NAV which corresponds to 1.832 million yearly on NAV from the half-year report. Some prepaid rents in the stated cash position might pare down the available cash, as most of that will have to be used for interest payments. Additionally, banks may have some requirements on cash on hand. NOI guarantees provided with the Domus and Duetto sales also could strain liquidity in the coming years. All in all, probably something like half of the liquidity is unavailable for loan repayments.

But wait, you say, can’t they borrow more from the bank on some of the assets such as Meraki or Europa? Probably not — that should reasonably have been the first go-to solution to limit the size needed to roll in the bond refinancing during the spring. If Europa continues to see operational improvements, there might be an out there in the future. But little help to limit liquidity issues should probably be expected from lenders at this specific point in time.

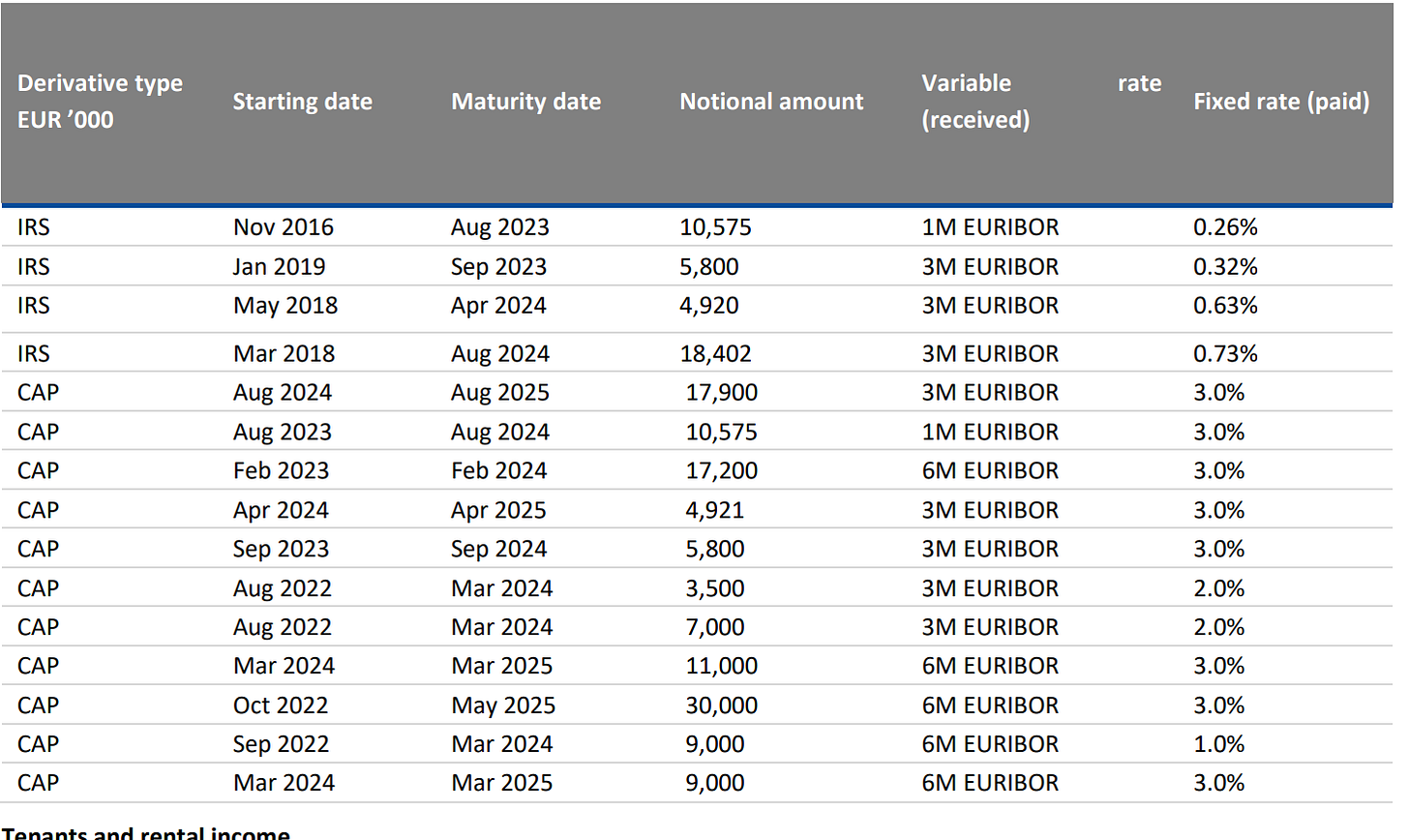

Now, let’s turn to the interest rate maturities

As seen here, quite a bit of cheap debt is rolling off its hedges or will be shortly, and there is no long-term hedges. In H1 2023, the annual running interest rate cost was 8.2 million, corresponding to a 4.2% interest rate.

If the entire bank debt portfolio is reset at 6% total interest cost — which will happen in the next year or so — and with the bond yielding 12% getting full effect on financing costs, interest rate costs will total 10.8 million. This may be undercounting as I base the 6% (of which ~4% is the EURIBOR) for bank loans on Kestutis Sasnauskas saying 200 basis points spread for bank loans was standard currently. However, BHF may be subject to higher spreads than Eastnine.

The 10.8 million can be compared to the 4.3 million of net rental income from last quarter, which does include some income from the Duettos which sere sold 6 June. Let’s call this 16 million annualized for a nice round number. That leaves us with an interest coverage ratio of about 1.5 in year. A level which would put BHF towards the bottom of the listed Swedish sector and it might leave a covenant issue with more individual loans, especially for the retail assets, seeing as the ICR covenant on Galerija Centrs is 1.8. Obviously, the overall level of the ICR is dragged down considerably by the high interest on the bond. But correspondingly, the overall ICR on the bank loans only is dragged up by the office buildings that cash flow better than the retail assets.

Please note that I am being generous both with longer term interest costs and with the current NOI. BHF themselves have guided for NOI of 13.5 million for this year. If that number is accurate, then costs are barely covered at all when including loan servicing and management fees. With more upside in interest rates, the fund would be mechanically forced to sell assets, even disregarding maturitites. There would also be no room for capex to counter the natural depreciation of the buildings. As you can imagine, NAV will melt away extremely rapidly under such circumstances.

A few thoughts on the appraised values on the books. There is a tug of war between the bears and bulls on this issue. The bulls think general inflation and specifically rent appreciation will more than make up for the lack of yield gap. The bears think stated book values are basically completely fake and that no real estate should ever have a cap rate at or below the cost of debt. Personally, I fall somewhere in between these two extremes. Both viewpoints have merit, and without rental appreciation the cap rate should be above the interest cost. But on the other hand, it’s not reasonable to disregard rent inflation if rents are either regulated to be below market rates or you have location scarcity, meaning the demand will pretty much always be strong over time. Also, just like cap rates by and large didn’t fall enough to fully reflect ZIRP forever, they may also account for the market consensus that we are currently above normalized rates, even though this could be wrong too (and we are certainly not above normal in a longer historical context).

Some of BHF’s retail assets seem to me like they have significant location scarcity value and they should perhaps yield lower than all office assets, even CBD office. Appraisers are slow to provide new marks when there are very few transactions. Also, the transactions that do occur early in a downturn tend to give a more rosy picture due to the selection effect. When sellers aren’t yet forced, they can pick and choose what bids they accept. And if a sale would not leave enough equity, they will never do sale until the equity holders are out of the picture.

There is one asset on BHF’s books that I would like to flag as being potentially overvalued for reasons other than interest rates: Meraki. This is a new office building that was opened to tenants about a year ago. It has stayed essentially 2/3 empty during this entire time and meanwhile its value on the books has not moved much and the appraiser assumes 5% long-term vacancy and values it essentially unchanged at 16.2 million. To me this seems unreasonable, considering that this is not an asset with a premium location or much if any positive letting. The bank seems to agree seeing as no secured loan has been granted on this property since finalization and repayment of the development bond last year.

Realistically, I would recommend unit-holders to push for a sale of the fund and be willing to accept a price significantly below NAV. I genuinely think that this has the highest chance of being the best course of action, but I do realize that this recommendation may have credibility issues coming from someone with an economic interest in a competing entity.

An alternative suggestion would be for the management company to escrow their fees with a third party until BHF shows two consecutive quarters of positive growth above the high-water mark of current NAV. Then they can be paid out the fees owed on a delayed basis. This would align the unit-holders and the management and show that management believes that the slow divestment route is a genuinely superior option for the unit-holders to a sale of the entire fund. If management didn’t believe that they could get back to the current NAV in a reasonable time frame, there would be no point in keeping the fund in business. Of course, I don’t expect any such arrangement to actually be implemented.

Unit-holders might also decide to tough it out and put up more equity to keep the fund going and allow for more measured handling of the current woes, but this also decreases NAV considerably and it leaves the — in my view — totally unreasonable drag from management fees.

BHF releases its Q3 report on Tuesday Nov 7. It’s should be interesting reading.